Human Rights Advocate

Leonard Feather frequently advocated for originality and openness in jazz. He supported equal rights and was of the view that musical talent was not confined to any particular race or gender. He often opposed systems or popular opinions that he believed limited the development of the art form. Feather did not consider jazz to be exclusively Western and traveled extensively, organizing concerts and engaging with musicians around the world. During these travels, he sought out local performances, showing consistent interest in regional jazz scenes.

Within the jazz community, there were differing opinions about the direction the genre should take. While some adhered to traditional views, Feather was known for encouraging new musical approaches. In 1933, he wrote to Melody Maker questioning why jazz had not yet explored waltz or 3/4 time. The editor dismissed the idea, but Feather pursued it, working with Benny Carter to record "Waltzing the Blues." The recording drew mixed responses, but over time, jazz in waltz time became more accepted.

Feather played a role in the early promotion of bebop, a jazz style marked by fast tempos and complex harmonies. The style was controversial at the time and often criticized by traditionalists. Feather's book Inside Bebop aimed to explain and contextualize the movement. He also encouraged RCA to record bebop music, though the label declined to use the term "bebop" for marketing, opting instead for "New 52nd Street Jazz." Feather occasionally used pseudonyms, including that of a friend, Billy Moore, in an effort to ensure his work would be judged on merit rather than personal association.

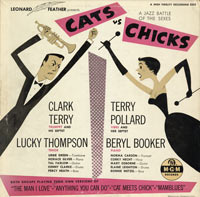

Feather addressed gender inequality in jazz. While female vocalists such as Billie Holiday and Sarah Vaughan achieved recognition, women were often excluded from other roles in the genre. After meeting pianist and singer Una Mae Carlisle in 1937, Feather highlighted her talent in an article for Melody Maker, where he introduced the concept of the "blindfold test" to challenge assumptions about musicians based on appearance. His early attempt to record an all-female band, The Hip Chicks, was not commercially successful, but a later project, Girls in Jazz, involved established female artists and received a more favorable reception. In 1954, many of these musicians were featured again on Cats vs. Chicks. While these projects did not achieve strong commercial results, they demonstrated the capabilities of female jazz instrumentalists.

Racial inequality was another concern for Feather. After moving from London to the United States, he encountered segregation and racism that shaped his commitment to civil rights. He supported the integration of jazz and promoted Black musicians throughout his career. Feather also participated in community programs and was involved with the NAACP, becoming vice president of its Hollywood-Beverly Hills chapter in 1963.